For February and March 2014, I’m heading back to India to expand my research and writing projects–developed at the Banff Centre last year–into a non-fiction book. The subject: child sponsorship.

What is child sponsorship, you ask? It’s a great multitude of things. It’s the dollar-a-day or so that you donate to a multinational charity to fund development programs in poorer countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It’s a complex partnership between donors, international non-profits, indigenous non-governmental organizations (NGOs), urban slums and rural villages, and, of course, children.

It’s a web of good ideas, good intentions, lots of money and a general desire to be a part of global change through local action in the fight against systemic poverty. It is also fraught with misperception, misinformation, misrepresentations and misappropriation. It sometimes looks pretty and feels good, and certainly millions of lives are changed for the better.

In my experience, how it works successfully is usually explained quite well. But how it works poorly–well, that’s where the untold story lies.

The children who write you letters and send you photos that you stick to your fridge are the symbols–the ambassadors to use the contemporary expression–of anti-poverty development. They are also children who have names, identities, struggles, successes, fears and doubts; children who are caught up, mostly unwittingly, in the vast child-sponsorship complex.

I don’t expect to change the world. I only want to tell a story that might change the way we look at it. It’s a story of a place and time; of inspiring people and a few who take advantage of power and privilege; of truth and deception; of our desire to change the world. I hope it’s a story for everyone.

Stay tuned. Contact me for more information.

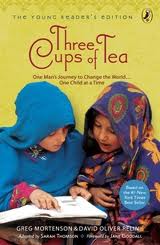

Photograph: Children at a NGO-supported community centre in Kandhamal, India. (Copyright Richard A. Johnson; photograph taken with the expressed permission of the children and the NGO.)